Famous Faces is a new gallery I just started on PhotoShelter. I needed a place to organize the images of famous and infamous people I have photographed during my career: George McGovern, George Wallace, OJ Simpson, Joe Louis, and Ronald Reagan to mention a few.

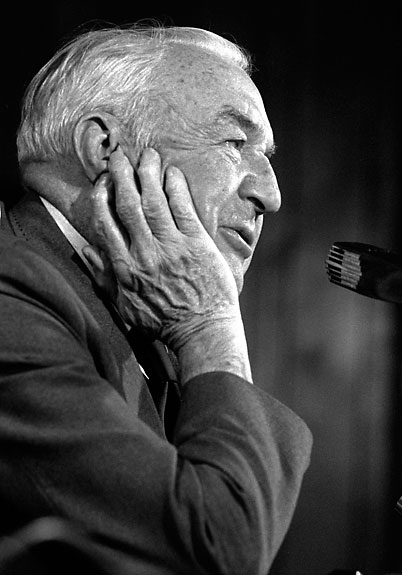

In 1975, recently retired US Senator Sam Ervin was on a speaking tour. Sponsored by The Modesto Bee and Modesto Junior College, he spoke in the MJC auditorium Wednesday night, November 19, 1975. I wanted to photograph Senator Ervin because he was a major player in the Watergate hearings. While I was in high school, my parents referred to Ervin as a Dixiecrat, I guess because he was a Democrat who defended the Jim Crow laws and racial segregation. I was taught that everybody was equal and watched my parents live that example. So my plan was to focus on the Senator’s investigation of the Watergate scandal that led to the resignation of Richard Nixon.

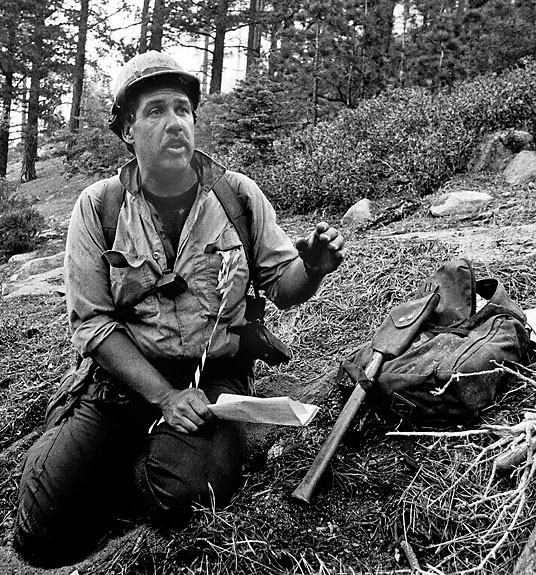

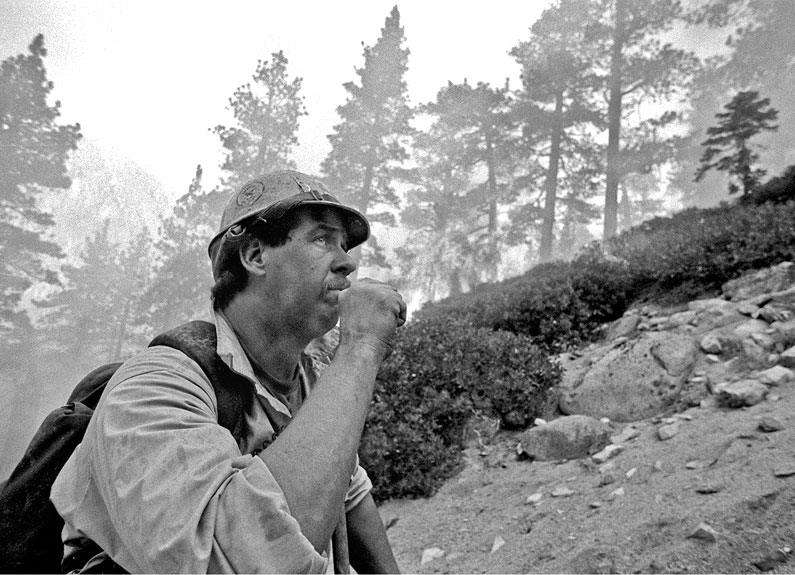

Wednesday afternoon, a press conference was held for Senator Sam in the MJC student lounge. I got the assignment, but the editor told me on the way out the door that the main picture was going to be of him speaking that night. I guess it didn’t occur to them how much closer I could get to the subject at the press conference and what an outstanding opportunity it was to make great images. I was only three to ten feet away from Ervin, whereas the MJC auditorium kept photographers forty feet away and on a lower plane due to the elevated stage. Several times, I jumped up onto the stage and photographed right on top of the subject. This approach has two drawbacks. First, you irritate the audience and second, you need a good helping of intestinal fortitude even to have the courage to risk it. Oh yea, in 1975 I could jump onto the stage.

At 79 years old, Sam Ervin was loaded with charm and wit. Using my trusty 105mm, I photographed him right, left and center. The three-light setup by the TV guys working together made for classic lighting. It is common for TV and still photographers to discuss lighting before a press conference.

With his country lawyer Southern drawl, Ervin delivered lines like “Unfortunately in this tragedy, the President failed to perform his constitutional duties to take care that the laws be faithfully executed. But the wisdom of the division of powers in government, made manifest by the Congress and the courts remaining faithful to their constitutional trust, enabled our country to weather one of the greatest storms any nation could have had.â€

The Senator listened carefully to a reporter’s question about freedom of the press and answered, “It’s absolutely essential. The men who wrote our Constitution put that guarantee in the First Amendment because they knew the full, free flow of information is essential to make government effective and to prevent tyranny over people’s minds. It’s not to benefit the press, but to give Americans the information they need.â€

Senator Sam Ervin impressed me. He looked directly into to my eyes, acknowledging I was a real person not merely a fixture in the room, which many politicians appear to think. To photograph him, I used a Nikon F2 with 105mm f 2.5 lens and Kodak Tri-X rated at 400 ISO and processed by hand in Ethol UFG film developer. I used moderate agitation to control the contrast because of the harsh quartz halogen lights.