Less than two months after the infamous Detroit riot of July 1967 in which the Michigan National Guard was called out, I was assigned to photograph California National Guard riot training for the Modesto Bee. At the time, I was still learning how to be a professional photojournalist, dealing with law enforcement and government agencies on a daily basis, listening to their view of events, and keeping the interests of the reading public first and foremost. Now I would be working with an arm of the military during a turbulent, conflict-filled time.

I had strong feelings about the Detroit riot, which lasted five days with 43 people killed. I also had strong feelings about the 1965 Watts Riots during which 34 people had been killed and over a thousand injured. I was in the Air Force at the time. Because I grew up in the Los Angeles area, the Watts Riots were close to home and I wanted to get down there to check things out. But that was impossible.

While I was in the Air Force, more than three of my four years were dedicated to the Castle Air Force Base Valley Bomber. As the Valley Bomber’s photographer, I got tons of experience making visual images to tell stories. It was easy for me to listen as the story subjects explained their job or department, its functions and operations. As they talked, visual ideas would instantly pop into my mind about how to tell their story. The process was uncomplicated, uncontroversial, and simple.

Now that I was in the world of photojournalism, I worked very hard to make the truth my mantra. Most subjects are controversial to one degree or another. Objectivity is essential. Achieving objectivity is an internal struggle that requires understanding my personal feelings while truly remaining open to the reality and facts I see.

The Modesto Bee provided me with some great mentors. Both Chuck Rodgers and Forrest Jackson instilled in me that we owed it to our readers to be truthful. They would kid me a lot, saying, “Don’t worry. Only a couple hundred thousand people will see your work. If you make a mistake there will be phone calls.â€

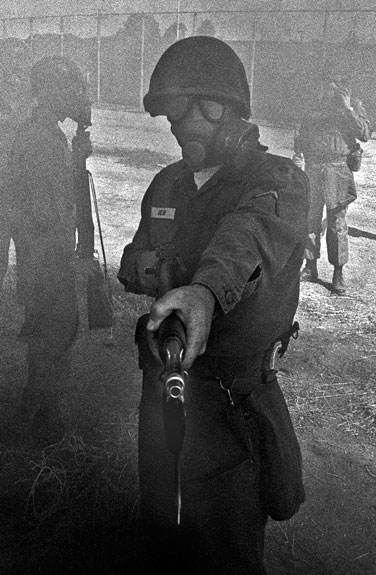

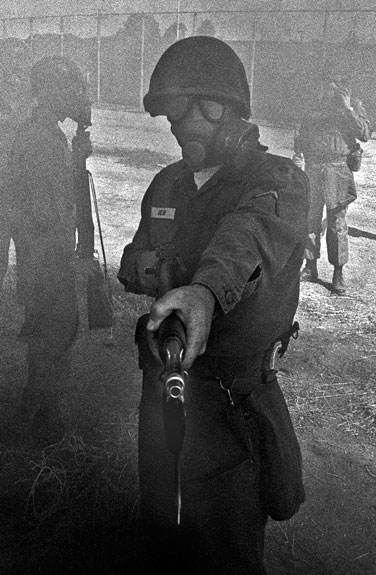

On my way to the assignment, a load of issues were going through my head. Most of my family has been in the military, so it was common knowledge in the family that using soldiers as riot control is dangerous. I didn’t want to glamorize the lethal approach to riot control, but I didn’t want to make the guardsmen look bad in any way. I knew that they were young men just doing their duty. At the same time, my military training told me that these infantrymen would be battle-trained and not prepared for civilian riot control. I concluded that my approach would be to show the training as seriously and accurately as I could. The images would tell the story and readers could draw their own conclusions.

Lucky for me, I had learned from my dad to be straightforward with everyone. When I got to the Armory I talked to the 1st sergeant. He gave me full access to the training (after hitting me up about how I could join the National Guard and make some extra cash). Out on the field, there were troops with fixed bayonets moving forward on a skirmish line. Purple smoke grenades were being shot from M14 grenade launchers to simulate tear gas. So I took off running to the center of the skirmish line. The troops kept coming and I kept shooting, using my Nikon high-speed thumb motor drive system. Everything came together in a few moments and then it was over. I photographed some other images including a practice interaction with a crowd of civilian-dressed guardsmen, but I knew that the skirmish line shot would tell the reader how dangerous it is to use lethally-equipped, battle-trained troops against our own citizens.

Back at the paper, the page one editor decided to use my single shot of PFC David Dean pointing his bayonet at me. As I shot, PFC Dean stopped and held his bayonet toward me. I only got a couple of clicks before he lowered his weapon as the Spec4 gave the “at ease†command. Then, being a good photojournalist, I asked him his name and rank.

In those years the Modesto Bee used “Bee Photo†for most bylines rather than the photographer’s name. On rare occasions when the editors felt images warranted a personal byline, the photographer’s name was used. PFC Dean ended up on A-1 and they gave me the personal byline with three more images on A-4. The next day instead of being happy about the personal byline, I complained about the inaccurate caption, which stated that the soldier was walking through tear gas. I asked Chuck, “How stupid do they think I am to say I would walk into tear gas to take a picture?â€Â He calmly told me, as I also learned to do in later years, that he would talk to the caption writer. Without a pause, he handed me a couple of new assignments. And like the good photojournalist I was becoming, I immediately took off to do them.

As expected, I caught plenty of flack about being so macho that I would walk through tear gas to get a picture. The friendly harassment was not unwelcome, but even more important was my satisfaction that I had made an image that told the story. Reader response was positive. Some were scared. And that was just as it should have been.